In Principle

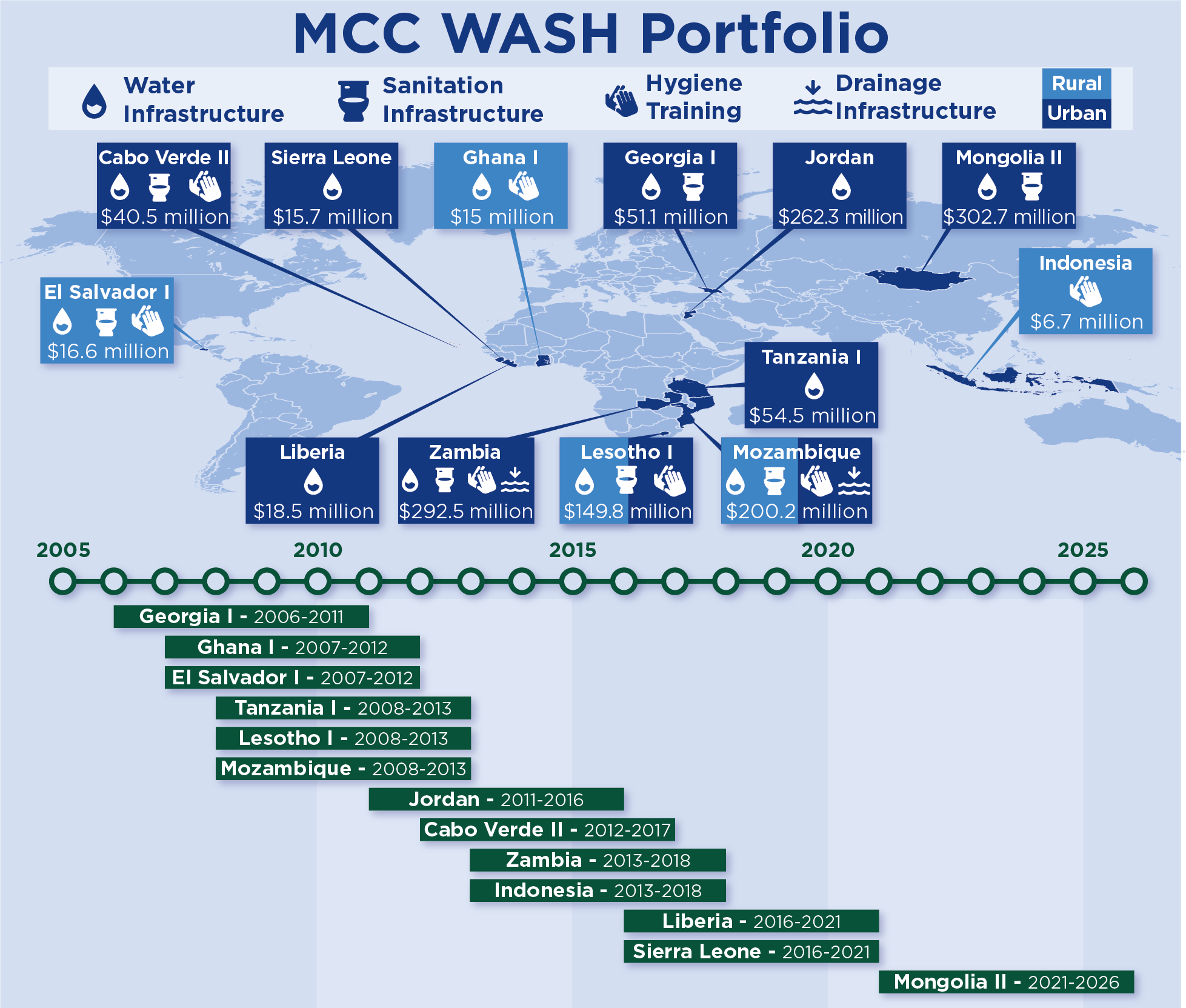

MCC has invested approximately $1.4 billion in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) programs since the agency was founded in 2004. Past investments spanned 10 countries and successfully constructed water supply systems, water treatment plants, water distribution networks, and wastewater collection and treatment systems. In addition to critical infrastructure investments, these programs funded policy and institutional reforms such as community awareness and training and capacity building for water utilities.Looking at the portfolio as a whole, MCC’s WASH interventions have targeted one, or a combination, of three themes:

- Inadequate supply of, quality of, and/or access to water

- Inadequate access to sanitation

- Excessive economic losses caused by flooding

In Practice

The last 15 years of designing, implementing, and evaluating WASH programs have revealed valuable lessons learned. Independent evaluations constitute a significant source of learning because they objectively measure and assess the achievement of targeted outcomes for each program in which MCC invests. To date, 12 final evaluation reports and six interim evaluation reports—for ongoing evaluations in the WASH sector—have been published. These evaluations report mixed results across MCC’s WASH portfolio. Program activities were generally completed as planned and the infrastructure installed was generally functioning as expected. However, the expected benefits to households and businesses mostly did not materialize. For example, in the rural program settings, time spent collecting water was reduced, but the programs had unrealistic expectations for the economic impact that the time savings would bring about. There also seemed to have been inadequate attention to human factors besides water supply that affect health outcomes. Finally, a mechanism for continued funding for the operations and maintenance of rural water infrastructure is key to sustaining the impacts of the investments.These evaluation findings, along with experiences implementing MCC’s WASH investments, prompted the lessons outlined in this paper and will hopefully lead to more consistently successful MCC WASH programs going forward.

Three Lessons from MCC’s WASH Portfolio

Lesson 1: Understand the specific problem that a WASH program aims to resolve and focus interventions accordingly around a clear and realistic objective

Know your problem and quantify it. MCC’s completed WASH program evaluation results indicate a lack of alignment between the activities that were implemented and the outcomes that were targeted. To design investments that demonstrate measurable results, MCC must identify a clear problem that contributes to the binding constraint to economic growth on the basis of evidence. MCC must then investigate that problem so that the program team understands its magnitude and dimensions in the context of the partner country or target region. Only then can the team properly design interventions to target the problem and accurately define the expected impact of these interventions.For instance, MCC’s urban WASH programs in Tanzania and Cabo Verde anticipated reductions in time spent collecting water; however, the evaluations revealed that the target population was not spending an economically significant amount of time collecting water to start with. The evaluations found a reduction of only a few minutes per week in Tanzania and no reduction in Cabo Verde. Similarly, several rural WASH programs were also justified on the premise that providing access to improved water sources would reduce diarrhea prevalence. However, the evaluations showed that diarrhea prevalence at baseline was relatively low. In short, a misdiagnosis of the problem, or misunderstanding of its magnitude, can result in overestimating the likely impact of the program and a potentially inefficient use of MCC funds.

Also, while often a water problem lies at the heart of a water-related binding constraint, in some cases, water is just one root cause of a health-related constraint. For example, under the right conditions, a water quality intervention could contribute to an objective of diarrhea reduction. However, if the program objective is to reduce stunting, it is less credible that water interventions alone would achieve the objective. Country teams should be careful to ensure that a WASH investment is necessary and sufficient to resolve the targeted health problem or is complemented by other activities to support targeted health impacts, using evidence to support the investment case.

Design for targeted results using program logic diagrams as a tool. Another issue is a disconnect between the program interventions and the targeted outcomes. The Mozambique rural water evaluation found that the program went beyond its infrastructure targets to increase access to an improved water source and even led to targeted households increasing their consumption of water from an improved source. However, the program did not achieve its aims of reduced diarrhea and increased incomes. The evaluation found that nearly half the tested samples of water stored in households was unsafe for consumption and suggested that household water storage practices posed a potential source of contamination in the household water supply. The program did not address household water storage practices and, in hindsight, the incorrect or unexplored assumption that households were safely storing water may have wiped out the expected benefits of providing them with an improved water source.

An additional challenge stems from programs that incorporate activities that are extraneous to the program logic. A case in point is the Water Smart Homes Activity of the Water Network Project in Jordan, which was not designed to address the problem at the core of the Jordan Compact objective. Thus, program ended up consisting of interventions that were unconnected to one another and to the rest of the compact.

Putting the Lesson into Practice: The Mongolia Water Compact included a Public Awareness and Behavior Change Sub-Activity to promote water sector sustainability for Ulaanbaatar. The need for this activity was not substantiated with evidence prior to compact signing, thereby presenting a challenge for defining its expected results. To address this issue, due diligence for this activity is ongoing, involving rigorous and statistically representative data collection on the socio-economic determinants of stakeholder’s choices, beliefs, and behaviors regarding water, tariffs, and payments. The data will help diagnose and respond to any potential problem.

Ensure that the program logic and design, cost-benefit analysis, implementation plans, and M&E Plan are in alignment. A misalignment between program design and the results modeled in the economic analysis can lead to confusion about the aim of the program and to evaluation results that are hard to interpret. Prior to 2018, when the Mongolia Water Compact was signed, every WASH program modeled health benefits as the pathway to economic growth. However, program designs focused almost entirely on WASH infrastructure and program teams rarely, if ever, included health programming expertise. Expectations about the results of these programs were frequently misaligned, with sector staff and the economist offering different perspectives on targeted results.

As an example, the cost-benefit analysis for the Tanzania Water Sector Project modeled health benefits through upgrades to water treatment plant infrastructure. There was disagreement within the project team about whether diarrhea reduction, followed by a reduction in stunting, was an appropriate expectation, given the interventions. It is critical that all team members have a common understanding of both the program objective and the means to reach that objective from the beginning. Moreover, the project evaluation also faced challenges in attempting to measure health benefits that were not clearly defined in terms of effect, size, and timing and were not necessarily calibrated to reflect the specific intervention. As a result of this misalignment of targeted and modeled results, the evaluation data collection and analysis became overly complex and the project’s accountability framework and results narrative became unclear.

Lesson 2: The ability of a program to achieve and demonstrate success depends on data quality and availability, and these issues must be explored in program development.

MCC WASH evaluations have shown that MCC has considerable work to do in this area and that this is a particularly difficult area for WASH interventions as much of the data is presumed to come from recipient utilities and is often not of the high standard required for a rigorous evaluation.Set a measurable objective. MCC’s investments in WASH have generally been successful in terms of implementation, in some cases completing works in excess of original plans, but have frequently been unable to demonstrate the achievement of outcome-level results, such as the program’s objective. In addition to issues considered in the first lesson, another contributing factor is the selection of program objectives that are not well or consistently defined and are difficult to measure cost-effectively. This is best exemplified by the Jordan Compact’s Water Network Project, which aimed to “improve the efficiency of network water delivery” by reducing physical losses in the system. It transpired that the utility was unable to measure physical losses due to how the water network was constructed. When implementation had progressed to a point that it became feasible to report on program results, MCC did not have good baseline or current data on either physical losses or the proxy of non-revenue water to assess and report on the effectiveness of the project. The overarching lesson here is that the main outcome and program targets must be feasible to measure cost-effectively.

Putting the Lesson into Practice: MCC has applied elements of this lesson in the development of WASH programs in the signed Mongolia II Compact and proposed Timor-Leste Compact to incorporate water engineering expertise on the evaluation team, assess the status of the WASH infrastructure, and assess network performance ahead of collecting customer-level data to assess the future expected results.

Collaborate to build and strengthen data systems. Once MCC recognized the need to better understand infrastructure and network performance to assess program results, M&E attempted to expand the scope of its data collection to include data more typically tracked by a water utility or water engineers. This included estimating end user water supply using pressure meters in Tanzania and ultrasonic sensors in Cabo Verde, and attempting to estimate water losses in the network in Jordan. However, these various data collection exercises proved challenging, as it can be costly and difficult to independently collect data that a utility should ideally be collecting itself.

In addition to recognizing MCC’s need for utility data for its own business purposes, the agency recognizes the value of supporting data-driven decision making in MCC’s partner institutions. While the idea of investing in a utility’s ability to monitor its own performance with reliable data is not a new one at MCC, the agency has not yet approached it in a way that expressly serves both the utility’s business needs and MCC’s, in terms of results measurement and reporting. There is, therefore, an opportunity for MCC to address both the above-mentioned data collection challenges and promote utility performance improvements by more explicitly incorporating utility data systems strengthening into program design.

Putting the Lesson into Practice: To at least partially address the need for better performance data, MCC now implements AquaRating in water utilities during compact development. AquaRating is a utility management tool that was developed in 2008 for the Inter-American Development Bank by the International Water Association, with the goal of strengthening the water and sanitation sector around the world.

Lesson 3: Design for water sector sustainability and persistence of benefits.

As with any investment, sustainability must be a key consideration in WASH investments if the anticipated benefits are to be maintained over a 20-year time horizon as MCC expects. In the WASH sector, sustainability of service provision and financial sustainability of the utility can be difficult to achieve while ensuring that everyone has access to adequate water supply and sanitation. MCC has tried to address each issue (cost recovery to the utility and affordability) separately, with the hope that a sound understanding of each issue will lead to the best solutions.Cost recovery is paramount when promoting sustainable water service for all. As part of standard due diligence, MCC conducts a financial assessment of the target utility both with and without the program. Compact investments (physical infrastructure and technical assistance) are then selected with an expectation that the financial viability of the utility would be improved.

Even after selection of investments to minimize the cost of water provision and sanitation services, the tariffs utilities need to charge to fully recover their costs may not be affordable to all, particularly the poor who are target beneficiaries of MCC investments. To accommodate this, MCC should identify and quantify the segments of the population that will require a subsidy to be able to afford service. Subsequently, MCC negotiates with the government to arrange the delivery of the subsidy to targeted users, directly or through the utility (with government funds so the utility is not required to provide the subsidy). Finally, MCC works with the government to agree on a cost recovery plan for the utility, including a tariff escalation schedule for the remaining customer segments.

Incorporate infrastructure operations and maintenance training and planning into program design. MCC’s infrastructure investments in both rural and urban settings have achieved varying degrees of sustainability, in terms of asset maintenance and the persistence of benefits provided by those assets. For example, in El Salvador, nine out of ten community water systems were still functioning six-to-seven years after installation. While service levels varied across sites, most of the physical infrastructure was still working and water was available at household taps. In Ghana, on the other hand, one out of six community water systems visited was still working six or more years after installation and water committees were not operational.

WASH programs should consider these sustainability challenges, in particular operations and maintenance capabilities when designing interventions, and should adequately prepare utilities to maintain the assets that they will be taking over.

Putting the Lesson into Practice: The Sierra Leone program attempted a ‘learning by doing’ approach to working with utility staff that promotes on the job capacity building. This challenge has also been anticipated in Mongolia, where program success is predicated on the fact that the utility, USUG, will need assistance in the day-to-day operations

Factor donor coordination into sustainability planning. Donor coordination has proven to be both a challenge and a strength when it comes to the sustainability of MCC’s WASH investments. Due to the strict five-year implementation timeline dictated by MCC’s founding legislation, MCC is not able provide long term incentives to our recipient countries for sustainable reforms. Additionally, it is challenging to fully implement complex sector reform activities within the five-year compact timeline. This means MCC sometimes needs to build on work already being done and that donors are needed for continued technical support after a compact has closed out. Donor coordination, while oftentimes necessary to create sustainable improvements in the water sector, has proven to be challenging in WASH infrastructure programs.

Putting the Lesson into Practice: In the proposed Timor-Leste compact, which is addressing stunting as a binding constraint to growth, MCC is actively coordinating with other donors to encourage them to fund health and behavior-change-focused interventions that will complement the infrastructure.

Implementation Lessons

In addition to the previously discussed lessons, which are largely motivated by the findings of the independent program evaluations, there are five important lessons gleaned from MCC’s implementation of WASH programs:Densely populated urban areas can be very hard to work in. Tremendous thought and planning have to be put into traffic management plans and phasing implementation in a manner that will cause the least amount of disruption. Engaging stakeholders is also very important as their cooperation ultimately makes implementation easier. Additionally, in these densely populated areas, there could be an increased need for resettlement compensation. In addition to the obvious increase in program cost, this also results in a longer implementation schedule.

Hiring of a reliable, competent consulting engineer to advise the Millennium Challenge Account (MCA) is essential to the success of infrastructure projects. It is important that MCAs have an advisor looking out for their best interests during implementation. The need for this was explicitly articulated in the evaluation for Lesotho, where it was determined that proper design reviews had not been completed for the infrastructure that was being constructed, which resulted in multiple implementation obstacles and the program objectives not being met.

Incorporating health and safety into WASH programs is paramount. MCC has faced difficulties in enforcing health and safety practices on infrastructure programs. This could be addressed by clearly specifying Environmental and Social Management Plan requirements like trench safety and traffic management in the contract document.

Use of sections (milestones) can incentivize contractor performance and control program management budgets. Sectional completion in projects will provide the implementing entity, or MCA, better leverage to manage contractor delays during construction. It will be more effective if each contract is divided into sections (milestones) and realistic delay damages are imposed and deducted from interim payments as and when contractors miss the sectional completion dates. This approach not only incentivizes the contractor to maintain the overall schedule, but also allows MCA to suspend portions of the remaining work and assign new contractors to do the suspended work.

Grant facilities present challenges for producing measurable impacts in WASH. MCC supported WASH infrastructure investments identified through a grant-making process in the Georgia I, Cabo Verde II, and Zambia compacts. In all three cases, inadequate definition of the program’s intended results presented challenges for MCC to demonstrate measurable economic impacts.

Conclusion and Continued Learning

MCC has learned a considerable amount in its 15 years of WASH investments and will strive to continue learning. The evolution of MCC WASH projects, from projects focused on the Millennium Development Goals (rural access, then urban access) to those focusing on increasing overall supply to meet demand in urban areas, is likely to continue as MCC operates in a changing global context, where water is becoming increasingly scarce. MCC plans to build upon the lessons identified in this paper by pursuing a broader learning agenda in the WASH sector. Future topics of exploration include:- Detecting constraints to growth in water scarce environments

- Modeling the economic impacts of water supply and wastewater projects in water-scarce environments

- Building utility capacity for network planning, operations and maintenance, and sustainable water and sanitation service provision

- Building data systems for program management and monitoring and evaluation (M&E) into WASH investments

- Ways to balance tariffs with cost recovery