Program Overview

MCC’s $475 million Burkina Faso Compact (2009-2014) funded the $58 million Rural Land Governance Project, which aimed to increase investment in land and rural productivity through improved land tenure security and land management. The project facilitated national-level legal reforms, strengthened newly decentralized land administration and land conflict resolution bodies, and conducted site-specific tenure activities to promote land registration. MCC theorized that these activities would lead to decreased land conflict and increased investment in rural areas.

Evaluator Description

MCC commissioned The Cloudburst Group to conduct an independent final impact evaluation of the Rural Land Governance Project. Full report results and learning: https://evidence.mcc.gov/evaluations/index.php/catalog/104.

Download the French translated evaluation brief.Key Findings

Legal and Policy Changes

- The project contributed to the Government of Burkina Faso’s passage and implementation of the 2009 Rural Land Law and the 2012 Agrarian and Land Reorganization Law.

- Select project-assisted legal reforms were sustained beyond the life of the project, while others were not.

Land Administration

- 47 land offices were established, and 2,167 of a targeted 6,000 customary land certificates were issued during the project.

- Additional land offices have been established post-project, although new and existing offices face challenges.

- Customary land certificates have continued to be granted, although not at the anticipated level due to the expense, the difficult and time-consuming process, and lack of information.

Land Tenure, Investment, and Assets

- The evaluation did not find evidence of an impact on household’s perceptions of land tenure security, land conflict frequency or occurrence, farmers’ investment decisions, or household assets.

- The evaluation did not find evidence of a significant positive impact on women’s property rights and empowerment outcomes.

Evaluation Questions

This final impact and performance evaluation was designed to answer whether the Rural Land Governance Project:- 1 Successfully implemented targeted legal reforms, operationalized land institutions, and distributed customary land certificates?

- 2 Operationalized the reformed land laws and regulations?

- 3 Improved land governance and administration?

- 4 Increased land tenure security, land conflicts, investment decisions, and income?

Detailed Findings

The findings of the final evaluation report build on the interim evaluation report results published in 2016.Legal and Policy Changes

SFR officer accessing commune-level APFR records system

Additional plans to reform the national land system, such as the introduction of a land information system to consolidate the operations of the large number of state entities working in the land sector, ultimately were not implemented. Geospatial infrastructure that was installed under the project to serve all mapping and surveying work nationally has not been broadly adopted at the commune level due to perceptions within the commune land offices that the system is technically burdensome and resource intensive. Due to the low demand for land certificates, tax assessment and fee collection through certificate processing is not a viable mechanism for achieving a sustainable revenue stream to support the decentralized, commune-level portion of Burkina Faso’s land administration system.

In the nearly 15 years since the Rural Land Law’s passage, evidence points to several unintended consequences, including delays in local infrastructure projects (which may be the result of stronger individual protections), land speculation, power vacuums and disruptions in local land governance, and continued inequity in land rights for men and women. These types of consequences have been identified in other studies of land administration reform in Africa.

Land Administration

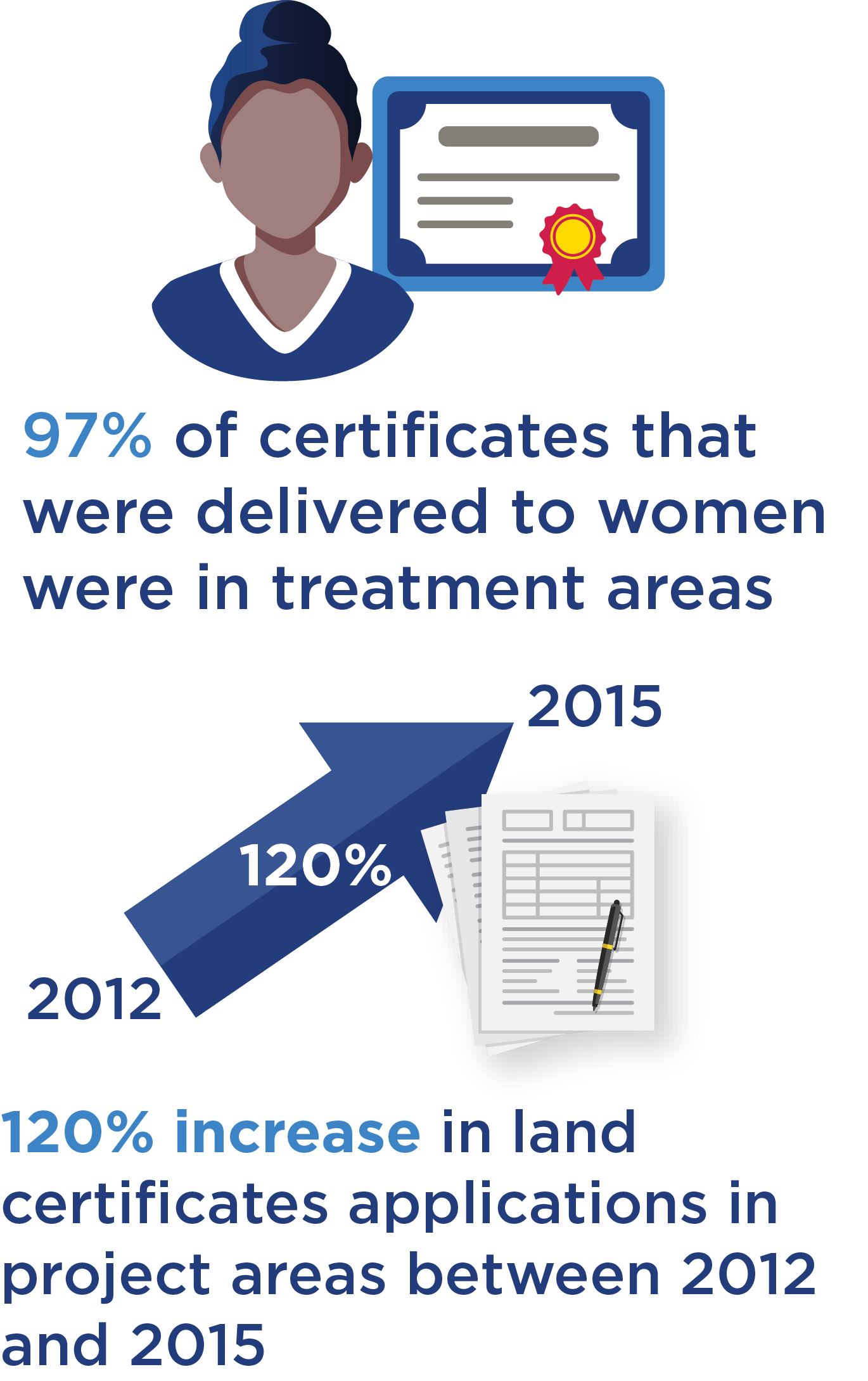

The number of households with land certificates remains low and well-short of project expectations. Factors may include demand-side reasons such as expense, a difficult and time-consuming process, insufficient information, or limited perception of need. Factors could also include sub-optimal operational performance of the local land offices where applications have been filed. However, there is evidence of an increase in certificate uptake in project communes. Between 2012 and 2015, land certificates applications rose in project areas by 120 percent. There is also a clear difference in demand for certificates from women, with 97 percent of the certificates delivered to women occurring in treatment areas.

Land certificates are more frequently used for conflict resolution (although conflicts themselves are relatively rare) and land investment in project areas than in treatment areas. Land transfers are also increasing in both project and non-project areas, although the absolute numbers are also small (272 transfers in a 10-year period in the study area). Most transfers have taken place where land speculation in peri-urban areas is occurring.

Land Tenure, Investment, and Assets

The evaluation did not find evidence that the project impacted households’ perceptions of land tenure security, land conflicts, producers’ investment decisions, and incomes and livelihoods. Additionally, respondents in project areas are more likely to express that their land rights are weaker than respondents from non-project areas. Respondents in project areas are also more likely to report concerns of future field conflict and land pressures facing their community.The evaluation did not find evidence that the project impacted women’s property rights or empowerment outcomes. Additionally, women respondents in project areas were more likely to perceive their land rights as limited than women in non-project areas. Finally, evidence suggests the project benefited large landholders (landholders in the top quintile of land plot size, holding 8.29 or more hectares of land). Large landholders in project areas were 32 percentage points less likely to be concerned that the government would expropriate their land than large landholders in non-project areas.

MCC Learning

- When supporting implementation of a partner government’s land sector reform, MCC should ensure that the government’s implementation includes ongoing messaging and engagement with key stakeholders.

- Land tenure insecurity does not necessarily imply widespread land conflict at the parcel level or dissatisfaction with existing conflict resolution processes.

- Evaluations should not hold the project accountable for outcomes that the project was not originally designed to address.

- When designing evaluations, MCC and evaluators should be thoughtful about the exposure period.

Evaluation Methods

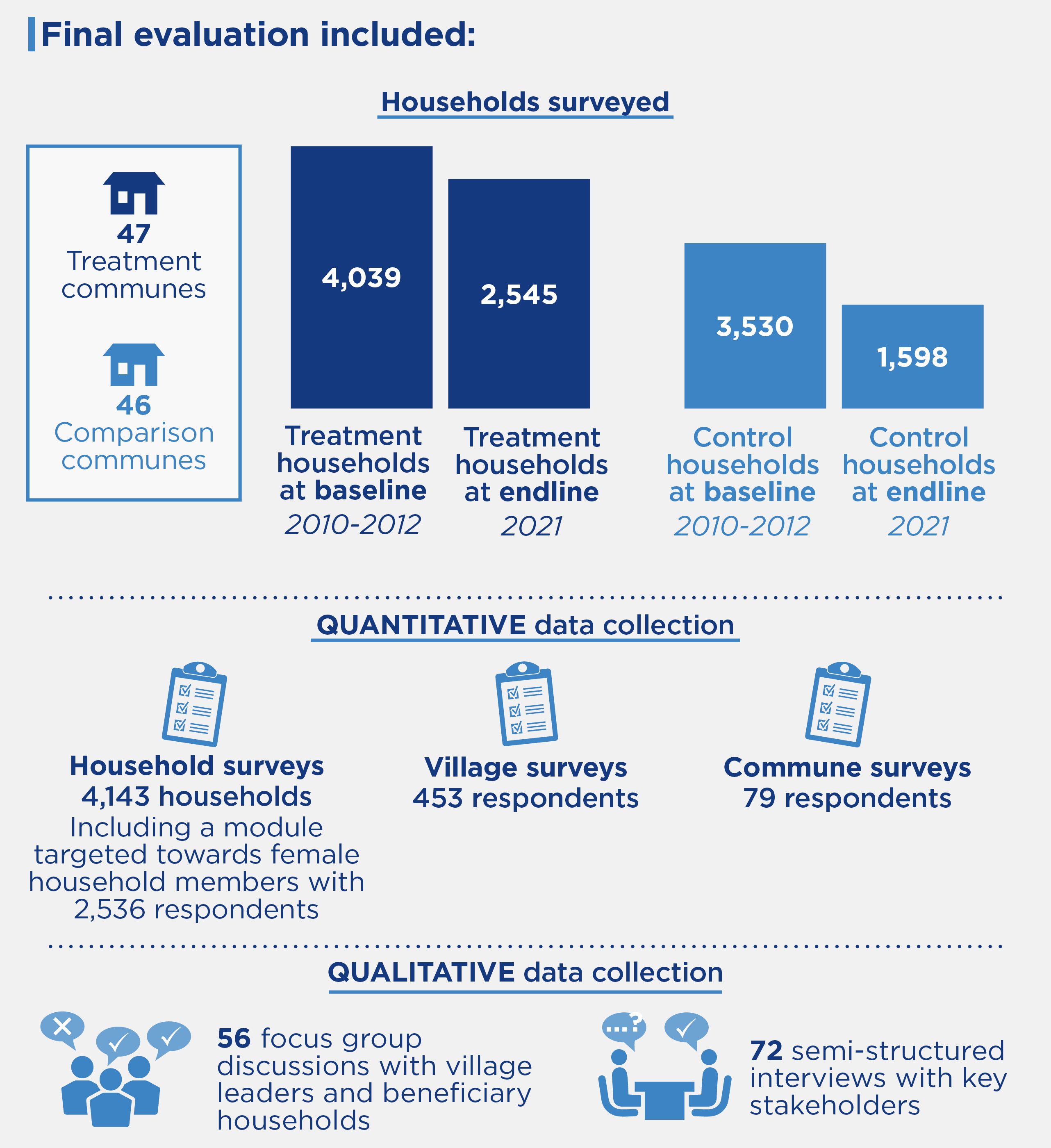

Primary quantitative data collection at endline included household surveys (4,143 households), including a module targeted towards female household members (2,536 respondents), village surveys (453 respondents), and commune surveys (79 respondents). Qualitative data collection included 56 focus group discussions with village leaders and beneficiary households and 72 semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders. This was supplemented by high-resolution satellite imagery, land administration data, and project documents.

Endline data collection occurred from November 2021-March 2022. Project implementation began in 2009 and ended in 2014, resulting in an exposure period of 7-8 years.

2023-002-2836