Project Summary

The 2011 constraints analysis identified insufficient qualifications of potential employees as a barrier to employment and wages. It was determined that a major barrier to target was weaknesses in the education system, particularly in STEM fields. Thus, the Improving General Education Quality Project began by approaching the problem at its starting point: at the general education level. There, the broadest and youngest group of Georgians would benefit from investment in improved school infrastructure, teachers and principals trained in student-centered instruction, and a curriculum policy feedback loop generated by regular assessment and evaluation of learning outcomes. By improving learning outcomes in the general education system, the project would contribute to economic growth through workforce development in Georgia.International best practice recognizes that education quality is achieved when the following components are present in an education system: knowledgeable and motivated teachers, strong school management, a well-designed curriculum with good teaching materials, student testing and performance evaluation, and a safe and conducive physical learning environment. At the time of compact signing, the Georgian public education system was underperforming in each of these areas. Teachers were underprepared with respect to both subject and pedagogical knowledge, and school directors lacked adequate professional training. Schools lacked teaching materials required for hands-on, student-centered learning. School facilities were in severe disrepair and lacked adequate heating or protection from the elements. Student performance was rarely assessed nationally. As such, the objective of the Improving General Education Quality Project was to improve education quality by targeting the physical learning environment, secondary school teacher subject knowledge and pedagogical skills, school management, and education assessments, with an emphasis on the STEM subjects.

Problems of quality were most pronounced in two specific areas: schools in rural areas and areas with larger proportions of ethnic minorities. Poor and ethnic minority children were more likely to start secondary education late and drop out early. Additionally, students in rural schools and poorer children also scored lower than students in urban schools on international assessments. Teachers in these targeted areas also struggled. Based on poor teacher certification rates, it was also noted that teachers in poor and ethnic minority schools were less qualified. For example, of the teachers that attempted the exams, 80 percent of teachers at schools in Tbilisi, the capital, were certified in their subject matter, compared to only 41 percent of teachers in the regions from more rural or remote schools. To address this, the general education investments targeted regions outside of Tbilisi, where poverty and ethnic minorities were concentrated.

Another glaring disparity was the issue of gender. The transition rates for girls from secondary to tertiary programs in STEM areas were low compared to boys, despite the fact that girls outperformed boys in these subject areas. Through specific interventions designed to benefit female students, the project aimed to increase girls’ participation in these fields.

The Improving General Education Quality Project was comprised of three activities: the Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure Activity, the Training Educators for Excellence Activity, and the Education Assessment Support Activity. Three Georgian government implementing entities were in charge of project management and oversight for the General Education Quality Project: the Educational and Scientific Infrastructure Development Agency (ESIDA) for the Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure Activity; the Teachers’ Professional Development Center (TPDC) for the Training Educators for Excellence Activity; and the National Assessment and Examination Center (NAEC) for the Education Assessment Support Activity. These three entities are under the purview of the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture, and Sport, and each played a key role in school infrastructure management, educator professional development, and education assessment activities, respectively. Although this approach introduced some delays and operational challenges for implementation, close collaboration with these organizations was an explicit strategy to build long-term organizational and management capacity in Georgia and to sustain project investments after the end of the compact.

Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure Activity

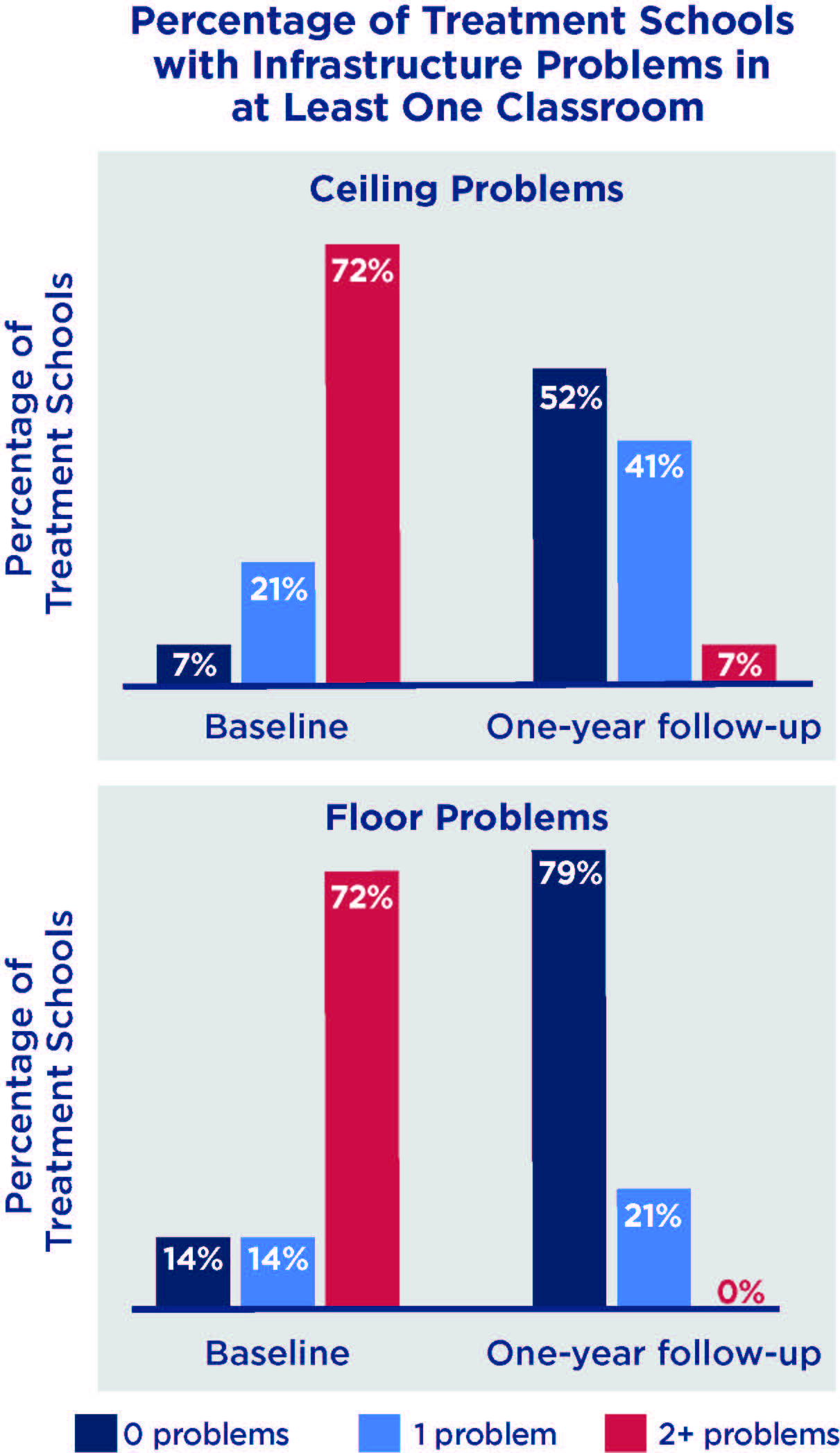

Most Georgian public schools were built during the Soviet era and were not properly operated or maintained. Aside from emergency repairs and partial refurbishments, much-needed large-scale repairs and new school construction had also been neglected and under-funded, especially since Georgia regained independence in 1991. In general, heating systems did not work and were poorly vented wood- or coal-burning stoves that generated smoke and poor air quality but not warmth in most classrooms. Leaky roofs contributed to the active decay of the buildings and systems, including collapsing ceilings, rotting floors, unsafe wiring, and decaying concrete and plaster. Lighting was limited and hallways and classrooms were poorly lit. Schools also generally lacked quality teaching equipment and learning materials. In sum, prolonged periods of insufficient maintenance and neglect resulted in school facilities that were in poor physical condition, adversely affecting student attendance, learning, and educational outcomes.Although there is not much international literature on the impacts school rehabilitation can have on student learning compared to new construction, U.S. literature indicates that physical infrastructure has an important impact on learning outcomes in general education. The characteristics that have the greatest impact are classroom temperature, air quality, lighting, and science labs/equipment.[[(1) Earthman, Glen I. (2002), School facility conditions and student academic achievement, Los Angeles CA: UCLA’s Institute for Democracy, Education and Access. (2) Earthman, Glen I. (2004), Prioritization of 31 criteria for school building adequacy, ACLU Maryland]] Better maintained and more conducive learning environments facilitate student learning and attract as well as retain qualified, motivated teachers. The Activity provided an opportunity to learn the extent of the impacts of school rehabilitation on student learning. In fact, the interim evaluation report showed significant improvements in the quality of classrooms and general school infrastructure, and that students and teachers were more satisfied with their learning environments. The final evaluation will examine the changes in student learning as a result of the improved infrastructure.

The Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure Activity aimed to rectify key aspects of the learning environment, including inadequate heating systems, poor indoor air quality, and inadequate lighting. At the school level, interventions undertaken through the compact to address these issues included: full interior and exterior rehabilitation of classroom and support buildings; new or significant upgrades to utilities such as electricity, water, and wastewater; and new laboratory classrooms. Designs to increase student health and safety in rehabilitated schools complied with domestic regulations and reflected international good practice.

A root cause of the poor quality of school infrastructure was the absence of any significant, systematic operations and maintenance programs in Georgia. Thus, the Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure Activity included a school Operations and Maintenance (O&M) component. This established a viable public-school O&M program at a national level. This program was intended to help address this root cause of the poor physical condition of the learning environment and promote the sustainability of Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure Activity investments in school rehabilitation.

Under the activity, the GoG, with and through MCA-Georgia, developed a national school O&M framework plan, established a dedicated national budget line for school O&M, conducted comprehensive inspections of most school buildings, developed software to plan and manage school O&M and minor repairs, designed and executed urgent repairs in two municipalities, and trained key personnel on school O&M good practices. These practices served to operate and maintain new assets installed at rehabilitated schools, such as wastewater bio-treatment plants at schools lacking connections to municipal wastewater systems. MCC supported these and other efforts through a dedicated school O&M Incentive Fund within the compact of up to $2,500,000. Through this incentive fund, the GoG committed funds for O&M, and subsequently MCC “matched” the GoG’s contribution through a commitment of compact funds. The O&M sub-activity evolved substantially over time, as described under the “Compact Changes” section of this report.

The Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure Activity:

- Rehabilitated 91 schools across the country;

- Introduced science laboratory classrooms and equipment in 91 schools; and

- Provided data, information, and planning to improve school operations and maintenance practices for all public schools in Georgia.

ESIDA, the government agency designated by the GoG as the implementing entity for this activity, created an 11-person project management unit (PMU) within the agency, focused exclusively on managing the MCC school infrastructure investment. The GoG funded all of the PMU’s operating costs as part of its country contribution to the compact. Although MCC was aware of capacity challenges within the agency, the decision to work through ESIDA despite these challenges was an explicit strategy aimed to build long-term capacity to sustain project investments after the compact. Unfortunately, staffing and capacity challenges and technical differences of opinion early on in implementation led to delays in the beginning of rehabilitation works. In response, MCC and the GoG decided to shift most of the responsibilities for building rehabilitation to MCA-Georgia, while tasking ESIDA with management and oversight of utility connections and ancillary works outside of the school building. MCC worked to keep ESIDA engaged in the school rehabilitation process from start to finish, with an aim to equip ESIDA with the knowledge and resources to properly maintain MCC-funded school sites post-compact term.

MCC and MCA-Georgia education and infrastructure specialists collaborated to improve the effectiveness, safety, and sustainability of science laboratories funded through the compact. The provision of science laboratory facilities, durable equipment and consumable supplies triggered significant curriculum revisions related to chemistry and physics experiments, modification of technical design criteria and installed systems for science classroom ventilation, the substitution of lower hazard chemicals for experiments, the refinement of supplies and experimental equipment to improve laboratory safety, and a comprehensive laboratory safety training program translated from English into local languages of instruction, including Georgian and Armenian.

ESIDA was also the implementing entity engaged in school O&M institutional reforms and executing Georgia’s country contribution to the school O&M Incentive Fund. During the final two years of the compact, the GoG started to implement decentralization reforms which resulted in ambiguity of institutional roles and responsibilities for school O&M. MCC focused more attention and resources on the O&M of compact-funded rehabilitated schools during the final two years of the compact, partly in reaction to this decentralization reform but also due to technical challenges obtaining data and information about more than 2,200 public school buildings that fell under the purview of the national O&M framework plan and system.

Training Educators for Excellence Activity

Some evidence shows that students have better learning outcomes when they have better trained teachers.[[Chetty, Raj, John N. Friedman, and Johnah E. Rockoff. “The Long-Term Impacts of Teachers: Teacher Value-Added and Student Outcomes in Adulthood.” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, working paper no. 17699. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2011.]] In the TEE Evaluation Design Report, the evaluators cite Hanushek and Chetty’s papers from 2010 which demonstrate that variation in teacher quality is causally linked to student learning outcomes.[[Hanushek, Eric. “The Economic Value of Higher Teacher Quality.” National Center for the Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research Working Paper 56. Washington, DC: Urban Institute, December 2010.]] However, the evidence on effect size is mixed. At the time of compact development, the GoG had established a framework for continuous professional development of teachers, including associated salary increases, in an attempt to improve teacher quality. The government entity responsible for teacher professional development, the Teachers’ Professional Development Center (TPDC), was charged with implementation of this framework, and needed support to transition from exclusively providing certification-oriented short-term, subject matter-focused trainings to facilitating continuous professional development. At the school level, it was acknowledged that school directors needed support, as well as strong educational leadership support for improved learning outcomes.The objectives of the Training Educators for Excellence Activity were to: (1) improve math, science, information and communication technology, and English teaching in order to improve learning in grades 7-12; and (2) improve school management. To accomplish these objectives, the activity offered training to all 2085 public school principals in Georgia, at least one school professional development facilitator per school, and all 18,750 secondary school STEM, geography and English teachers in the country. The activity aimed to have at least 74 percent of these educators complete the full training course, taking into consideration the length of the trainings and turnover of teachers. The full training program was delivered over a multi-year period and included several cycles of in-person training modules for teachers and principals, complemented with tasks and activities between the modules. The trainings covered leadership skills, student-centered pedagogy approaches, innovative and interactive teaching methods, subject matter expertise, science lab health and safety, and gender bias.

Another aspect of the activity was the provision of trainings in minority languages. The Georgian population is ethnically diverse and in many instances members of minority groups have limited command of the Georgian language. Limited language comprehension affects student’s access and ability to actively participate in a mainstream education. In addition to Georgian language schools, the GoG funds public schools where the primary languages of instruction are Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Russian. Prior to the compact, ethnic minority population teachers had fewer opportunities than their ethnic majority counterparts to participate in professional development programs due to language barriers. Teachers and principals at these schools did not have access to the same training materials or trainers as Georgian-speaking teachers and principals, which furthered their exclusion from the education quality gains that the government was supporting. Notably, for the first time in Georgia’s history, through the TEE Activity, ethnic minority teachers and principals received trainings in minority languages (Armenian, Russian, and Azerbaijani) that were identical in content and format to the trainings that Georgian-speaking educators received, delivered by minority language-speaking trainers. TPDC targeted 2,177 minority language teachers, 213 school professional development facilitators and 213 school directors.

The Training Educators for Excellence Activity was expected to improve student learning through improved teaching and management of schools. A dedicated unit (PMU) within TPDC was responsible for overall implementation of the activity. Delays in forming the PMU, as well as early management challenges, caused the initial roll-out of the trainings to take place later than originally planned. Once on board however, the TPDC PMU staff had strong technical and managerial skills, and the activity was quickly back on track, as the PMU successfully managed and oversaw numerous, complex trainings and follow-on activities.

The structure of the trainings required a significant time commitment from school principals and teachers. School principals and professional development facilitators were trained through a three-part “Leadership Academy” training program. TPDC delivered this program regionally, which included up to 160 hours of intensive, face-to-face engagement. In order to foster exchange and collaboration among principals, those who attended the Leadership Academies were also required to attend quarterly meetings. At these meetings, principals from the same regions were able to discuss common questions and concerns, reinforce the techniques and approaches acquired during trainings, and hold one another accountable for completing assignments from the trainings. TPDC also organized two annual principals’ conferences which brought together school principals from across Georgia to share knowledge and best practices.

Teacher training consisted of intensive “core” and “subject matter” modules. This included 60 hours of face-to-face training on student-centered, participatory approaches to learning, complemented by additional non-contact hours. TPDC also organized regular study group meetings for teachers to foster “communities of practice” for STEM teachers at the school level, while allowing teachers to reflect on the material presented during the trainings. TPDC developed 16 hours of lab safety and experiment methods training modules with the support and guidance of the US-based Lab Safety Institute. These trainings were delivered to all STEM teachers in schools where new science labs were installed through the Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure Activity.

Integrated into the teacher and principal trainings were sessions on gender and social inclusion theory and practice, which TPDC developed through a partnership with UN Women. As teachers and principals play a vital role in the early empowerment of girls by creating an equal, inclusive environment for STEM learning, this additional training component aimed to have a strong multiplier effect. Teachers and principals were challenged to rethink cultural norms about the preference of boys and young men in the STEM fields, which then translated into more inclusive teaching styles. These investments aimed to increase the number of better educated girls able to pursue vocational and STEM higher studies.

After two years of training module development and activity design, implementation began in spring 2016 with trainings of trainers. Although attendance was optional, participation rates in both teacher and principal trainings were high. TPDC trained and certified more than 300 principals and teachers to serve as trainers to deliver the modules nationwide. By the end of the compact, approximately 18,000 teachers participated in compact trainings, nearly 12,000 of whom completed the full program and received a certificate. Over 2,000 principals and another 2,100 school-based professional development facilitators completed at least one course in the training program.

The interim evaluation report showed that by 2018, 93 percent of school directors attended all five training modules, and 82 percent of teachers from the first cohort completed the training. The training modules developed through this activity were subsequently integrated into the GoG’s continuous teacher professional development system, which provides salary and career incentives to encourage teachers to pursue professional development. The nationwide reach of this activity is the driver of the compact’s beneficiary number of just over 1 million students over twenty years.[[The closeout estimate of the beneficiaries is preliminary at the time of this report.]] Teachers who received the training are considered participants of an MCC project, and the beneficiary number represents the students who would benefit from better trained teachers for years to come, as a result of improved learning outcomes and therefore higher long-term earnings, as outlined in the description of the ERR for the TEE Activity.

The interim evaluation found that almost all school directors and teachers liked the trainings and saw value in participating. School directors reported that the training improved their capacity to provide instructional leadership through curriculum guidance, classroom observation, and supporting teachers’ professional development. Teachers also became more confident in their ability to teach higher-order thinking skills, promote cooperation through group work, and use lesson plans that include formative assessments and differentiated instruction for students with different abilities. However, there was minimal evidence of immediate changes in teachers’ classroom instruction practices, and in focus groups some teachers voiced concerns about the amount of time and effort needed to implement these practices consistently.

Education Assessment Support Activity

In support of improved education outcomes, the GoG committed to fostering enhanced, modern, and results-oriented schools. Assessment of student learning provides critical information on the operation of schools regarding the knowledge, attitudes, and skills obtained by learners as a result of their exposure to schooling. However, little work had been done to evaluate the performance of students across the nation. Education assessment results were mostly used to evaluate teachers, rather than to help educators better address the needs of their students. The National Assessment and Examination Center (NAEC) was also in need of support to ensure Georgia’s participation in international assessments.Through this activity, the compact provided financing and technical support to NAEC to carry out national and international assessments. The compact provided funding to support national assessments of secondary school student achievement in math, biology, chemistry, physics, and Georgian as a second language. The compact also funded Georgia’s participation in two rounds of international assessments including the Teaching and Learning International Survey, the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, and the Program for International Student Assessment. Through its country contribution, the GoG also funded the country’s participation in the Electronic Progress in International Reading Literacy Study. The compact also funded additional training and salaries for key NAEC staff, as well as tools for school evaluations.

Data generated by national and international assessments enabled policymakers to observe trends in student achievement, both nationwide and as compared to other countries. Based on assessment outcomes, the Ministry of Education and Science would then be better positioned to plan, adjust, and implement policy decisions to support improvement of the teaching quality. In the final year of the compact, when there was large turnover within NAEC, particularly in the assessment division, the compact supported the training of new staff. By the end of the compact term, NAEC had completed two rounds of the three international assessments and six national assessments.

In addition, reports on assessment results were published and disseminated, and a national conference was held in 2017 to discuss the results of the international assessments. This conference was an important first step for the government, policymakers, and other stakeholders to demonstrate their willingness to define policy priorities based on assessment results. Early signs indicate that this activity is informing policy changes and shaping foreign assistance in the education sector. For example, the most pronounced finding of the assessments was a growing performance gap between students in urban and rural areas, with students in urban areas doing far better academically. As a result, during the unveiling of its education sector strategy in 2018-19, the GoG announced it would prioritize support to improve learning outcomes for students in rural areas and other socioeconomically disadvantaged students. In addition, in 2019 the GoG announced that, as a result of this finding, “school leaving” exams were determined to disproportionately impact ethnic minority students and were therefore abolished. Assessment results are also being widely used by other donors, such as USAID and the World Bank, to inform their new education assistance programs.

Project Sustainability

Sustainability was incorporated into the Improving General Education Quality Project from its inception. The GoG’s budgetary contributions laid the foundation for sustaining MCC’s investments in the future. Close partnership with implementing entities (ESIDA, TPDC, and NAEC), an approach that was also successful in the first Georgia compact’s Energy Rehabilitation Activity, was intended to help develop long-term institutional capacity in Georgia. From the start, this capacity building was an important way to increase the sustainability of the compact.Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure Activity

The Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure Activity depended on collaboration with public schools and the Ministry of Education, particularly ESIDA. ESIDA was charged with implementing a nationwide O&M plan for all public schools, including those rehabilitated by MCC. During the compact term, ESIDA also assumed responsibilities for funding, designing, and connecting utilities, including water, electricity, and natural gas supply, as well as wastewater disposal, fencing, gates, and asphalt at school sites. Though it was at times challenging to align ESIDA’s roles and responsibilities for school construction, rehabilitation and operations and maintenance with MCA-Georgia school rehabilitation works timelines, ESIDA generally fulfilled responsibilities in these areas, and as a result, made a meaningful contribution to school rehabilitation. Following completion of MCC-funded rehabilitation works and prior to school re-openings, ESIDA-funded site perimeter fencing and paving work was generally completed and ESIDA-financed utility connections to power and water were finished. Schools were fully operationalDuring the last two years of the compact, government educational reforms focused on decentralizing school management. This decentralization introduced ambiguity as to which entity would be responsible for, among other things, school O&M funding, prioritization, and execution of O&M responsibilities. The revised National Whole School O&M System Framework Plan, developed and updated under the auspices of MCA-Georgia in January 2019, reassigned some roles and responsibilities from ESIDA to municipalities. Although MoES verbally expressed support and commitment to school O&M throughout the compact term, the GoG had difficulty committing and obligating funds identified for matching by the O&M Incentive Fund defined by the compact and undertake other actions required to meet the two school O&M conditions precedent in a timely manner. A high degree of turnover at MoES during compact years 4 and 5 compounded the lack of ownership and limited capacity to produce results related to systematically improving school O&M nationwide. In hindsight, establishing a viable, national-scale school O&M system over a five-year timeframe may have been overly ambitious and more difficult than anticipated for the GoG to sustain after the end of the compact. The role of ESIDA continues to evolve, as the GoG institutionalizes changes to roles and responsibilities within the general education sector.

The Millennium Foundation, the successor entity to MCA-Georgia and funded by the GoG, is supporting the sustainability of compact investments in school infrastructure. This entity is tasked with monitoring the quality of compact-funded school rehabilitation works and addressing defects that arise, as well as contributing to the implementation of the school O&M plan. The Millennium Foundation continues to raise the problem of insufficient nationwide school O&M financing, to ensure that a new funding structure for Georgian public schools will allocate specific funding for O&M purposes. ESIDA’s O&M budget helps guarantee that the public schools rehabilitated with compact funds are relatively well-maintained, however, the overall policy of school funding needs revision.

Training Educators for Excellence Activity

Sustainability was built into the Training Educators for Excellence Activity from the start by integrating all training activities into the GoG’s own teacher professional development system and building the capacity of TPDC staff to manage the system after the compact.After the compact, TPDC maintained responsibility for continuing to manage teachers’ professional development. In order to be financially sustainable, the compact also funded the development of online modules that would allow TPDC to deliver the same training content online at a significant cost savings. TPDC had already tested those modules and built capacity through delivering the online trainings to other non-STEM teachers before the compact end date. As future advances in the STEM fields are made, TPDC plans to continuously update the content of subject matter modules. In addition, in November 2018, TPDC began scaling up delivery of the core pedagogy modules developed through the compact, registering over 9,000 non-STEM teachers using its own resources. To ensure the sustainability of the teacher study groups formed during the trainings post-compact, TPDC provided grants to chemistry, biology, and math teachers’ associations. All of these follow-on activities were designed to ensure that compact investments are sustained and have a system-wide impact on future generations of Georgians.

Other donors will also continue to support educator professional development in Georgia. The Training Educators for Excellence Activity was designed in close coordination with USAID’s Georgia Primary Education Project, which ended in 2018. This program provided student-centered training to primary education teachers. MCC participated as a member of the working group to prepare a document appraising USAID’s new general education project Achieving Student-Centered Education for a New Tomorrow (ASCENT), which was launched in January 2020. ASCENT is focused on the primary grades and teachers’ and school administrators’ in-service and pre-service education and will therefore both complement and help sustain MCC’s TEE investments. The Peace Corps plans to use the English teacher subject-matter modules developed through the compact as well.

Education Assessment Support Activity

The compact aimed to ensure sustainability for the Education Assessment Support Activity by integrating activities into NAEC. Activities were led by NAEC personnel, with technical assistance provided as needed to build additional capacity within NAEC to administer testing, evaluate results, and share findings. Over the course of the compact, NAEC staff executed a number of national and international assessments, which provided them with the skills and experience necessary to continue them without MCC support. The GoG has expressed its intention to continue carrying out periodic national assessments and to participate in international assessments post-compact. One of the key objectives of the USAID ASCENT program will be to support the GoG in using data and evidence, including the results of education assessments funded through the compact, to inform policy decisions.Economic Analysis

- Original Compact Project Amount: $76.5 million

- Total Disbursed: $70.7 million

Estimated benefits at compact closure corresponded to $70.7 million of MCC project funds, $17.0 million of country contribution project funds as well as administrative and M&E costs, which are all included in the cost-benefit analysis.

| Project | Activity | Estimated Economic Rate of Return over 20 years[[For education projects MCC’s economic analysis typically considers 20 cohorts of students that are followed for at least 20 years, in order to capture the long-term benefits that are realized during their working years. This is consistent with the economic analysis for other sectors as the 20-year time horizon begins when the investment is completed, and the first cohort enters the education program and includes the cohorts that enter during the 20-year time horizon. Since the benefits are delayed and obtained during their working lifetime, the economic analysis includes at least another 20 years for each cohort to ensure those benefits are captured.]] | Estimated beneficiaries over 20 years[[The total number of beneficiaries of the Improving General Education Quality Project is less than the sum of the beneficiaries of the project’s three activities because it is adjusted for double counting. The beneficiaries of the Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure Activity are a subset of the Training Educators for Excellence Activity.]] | Estimated net benefits over 20 years | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improving General Education Quality Project | At the time of investment decision[[Economic analysis data (estimated ERRs, beneficiary counts, and net benefits) presented for investment decision and entry into force cost-benefit analysis (CBA) models may not be comparable to compact closure data, as earlier CBA models for the Georgia II Compact were not extensively peer reviewed and only the EIF CBA model for the Industry-Led Skills and Workforce Development Project was published on MCC’s website.]] | 13% | 1,700,000 | $28.6 million | |

| Updated at entry into force | 11% | 1,700,000 | $7 million | ||

| Updated after compact closure | 15.5% | 1,067,817 | $78.9 million | ||

| Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure Activity | At the time investment decision | 8%[[As shown in the table, the project-level ERR was above MCC’s 10% hurdle rate at the time of the initial investment decision (13%). For this Activity, MCC wanted to design school selection to ensure a balance between school size (a key variable for the ERR) and equity (as measured by the proportion of socially vulnerable students). Given the 13% ERR for the project, an activity-level ERR of 8% was approved to meet the desired targeting strategy.]] | 423,000 | -$8 million | |

| Updated at entry into force | 10% | 348,000 | $23,000 | ||

| Updated after compact closure | 8.1% | 66,266[[This beneficiary count applies to only 10 cohorts of students due to reduced operations and maintenance (O&M) commitments that reduced the sustainability of the investment. All other beneficiary counts presented for the ILEI Activity and Improving General Education Project apply to 20 cohorts of students. For economic analysis, direct beneficiaries are students who graduate from with project schools and become employed, resulting in increased incomes. Total beneficiaries, which are reported in the table, is calculated by multiplying the direct beneficiaries by the average household size in Georgia (3.4).]] | -$13.2 million | ||

| Training Educators for Excellence Activity | At the time of investment decision | 27% | 1,700,000 | $60.9 million | |

| Updated at entry into force | 18% | 1,700,000 | $19.1 million | ||

| Updated after compact closure | 26.5% | 1,067,817 | $104.1 million |

The economic logic underpinning the investment decision and EIF cost-benefit analysis (CBA) models used to calculate the ILEI Activity ERR remains largely the same in the compact closure CBA model. However, updated data based on CBA model peer review, evaluation reports, and new information on GoG O&M commitments resulted in a reduction of the closeout ERR to 8.1%.

The main benefit stream from the ILEI Activity is an increase in educational attainment that results in increased probabilities of employment and increased long-term earnings. Increased time on task and reduced student absenteeism, as a result of an improved learning environment, are the channels through which student learning results are expected to improve.[[While there are potential health benefits associated with rehabilitated schools, these were not quantified in any CBA models for the Activity; in this sense, the reported ERRs are conservative.]] These results are measured using completion rates (for 12th grade, reflecting graduation from upper secondary school) and transition rates (from upper secondary to TVET and from upper secondary to university) for secondary school students in Georgia and income, labor force participation, and employment data by school completion level. Due to weak evidence on the effects of school rehabilitation on education quality and educational attainment,[[The 2019 Evaluation Interim Report for the Georgia II Improving General Education Quality Project’s School Rehabilitation and Training Activities by Mathematica (Interim Evaluation Report) summarizes the existing literature on school rehabilitation.]] the closeout CBA model assumed more conservative increases in completion and transition rates for students in project-rehabilitated schools.[[Notes on previous economic logic indicate an initial assumption of 20% increases in transition rates. The Interim Evaluation Report indicates the assumption on transition rates had been reduced to 10% but included a transition from lower secondary to upper secondary. In the closeout CBA model, the transition from lower to upper secondary education is not modeled due to nearly universal transition out of 9th grade and into upper secondary school in the data; instead, the model assumes a 10% increase in graduation from upper secondary school and applies higher education transition rates to the set of graduating students.]]

Improved learning outcomes and increased educational attainment leads to increased income through three pathways: (i) students who have higher educational attainment are more likely to be employed; (ii) students who have higher educational attainment earn more income when employed; and (iii) students who experience an improved learning environment in project-rehabilitated schools are assumed to earn higher incomes relative to without-project school students with the same level of education. The closeout ERR decreased from earlier estimates in part because of updated data on baseline graduation and transition rates, which were higher than initially thought. Updated data shows nearly universal completion from lower secondary school, which leaves little room for improvement among students who would not have completed 9th grade without the project.

The largest change in assumptions in the ILEI closeout CBA model reflects updated estimates on GoG commitments to post-compact O&M. This resulted in an assumption of a reduced project life, where benefits in the CBA model extend to only 10 cohorts of students instead of 20. While this reduced the number of beneficiaries by half, it did not negatively affect the ERR since the reduction in the benefits are offset by the reductions in O&M costs.

The ERR for the Training Educators for Excellence (TEE) Activity decreased from 27 percent at the time of the investment decision to 18 percent just after entry into force. This change reflected the evolving project design and additional research that suggested that the degree to which the training would affect students’ grades was less than originally anticipated. Although fewer teachers were expected to be trained, updates in class sizes meant that the same number of students were expected to be reached. This did not change the number of Georgians that benefited from the program.

The main changes to the closeout CBA model, and the cause of the more than 8 percentage point increase in the ERR, are from using updated data from project completion reports, interim independent impact evaluation, the latest national labor force and household data, and two comprehensive literature reviews. The main benefit stream for the TEE Activity is a relative increase in wages as a result of improved student learning. The interim evaluation demonstrated that the TEE Activity was implemented well, and its design was consistent with many of the most effective practices identified in MCC’s updated literature review. This supported the use of a slightly larger increase in test scores for the closeout CBA.

The next step in estimating the impact of these efforts are to consider how improved learning outcomes will result in increased future earnings. The closeout CBA updated estimates of long-term earnings based on more recent literature on the subject. The positive change in these two key variables (i.e., student learning and incremental wage increases) contribute to the large improvement in the closeout ERR for the TEE Activity.

There was no ERR estimated for the Education Assessment Support Activity. The costs of this activity are included in the project-level ERR calculations, but no specific benefit streams were included in the CBA models due to the lack of rigorous literature available to support its inclusion. While not included in the economic analysis, MCC and the GoG agreed on the importance of the activity, which aligns closely with MCC’s commitment to data collection and the use of evidence for decision making.

Evaluation Findings

The Improving General Education Quality Project aimed to improve the quality of public STEM education in grades 7-12. The project invested in rehabilitating education infrastructure and constructing science laboratories in targeted schools. A one-year sequence of training activities was provided to STEM educators and school directors on a nationwide basis. While the effects of the project are assessed by one evaluation, because the Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure and Training Educators for Excellence Activities were implemented separately and on different schedules, the evaluation uses two evaluation methodologies implemented on different timelines, one for each of the activities. The Education Assessment Activity has been closely monitored, but because the assessment portion was not integrated in the logic of the Training Educators for Excellence Activity, as originally planned, it was not included in the evaluation design.The Improved Learning Environment Infrastructure Activity’s portion of the evaluation aims to measure the effect of improved infrastructure on attendance, enrollment, retention rates, and test scores. Specifically, the evaluation seeks to answer the following evaluation questions:

- Did school rehabilitation deliver improved facilities?

- What are the impacts of rehabilitation on the school environment, including temperature, lighting, equipment, and infrastructure maintenance?

- What are the perceptions of students, parents, teachers, and school directors about the effects of rehabilitation on safety, comfort, and the extent to which time in school is used effectively for learning?

- Did training initiatives for teachers and school directors succeed in delivering training on a nationwide basis?

- To what extent do school directors perceive that their instructional leadership and school management skills have changed as a result of the new training intervention?

- To what extent do teachers perceive that their pedagogical and classroom management practices have changed as a result of the new training intervention?

- Did teacher training modules improve teachers’ knowledge of and willingness to use practices related to student-centered instruction, formative assessments, and improved classroom management?

School Rehabilitation

- In the first phase of school rehabilitation (29 schools), students experienced large improvements compared to baseline in heating, lighting, sanitation, building quality, and access to science laboratories and recreation facilities.

- Students and teachers agreed that these improvements addressed barriers to using classroom time effectively on instruction.

- The final report will estimate impacts for all rehabilitated schools and measure whether infrastructure upgrades improved learning outcomes.

-

- The teacher training component was successfully delivered on a nationwide scale, with high completion rates for school directors and teachers.

- One month after the one-year training sequence concluded, teachers reported that they had improved confidence using student-centered teaching practices, and school directors reported that they had increased delivery of instructional leadership. However, there was little evidence of immediate changes in teachers’ classroom instruction practices.

- Those involved in the design and implementation of the teacher training component anticipate that further changes in instructional practices could develop over time. The final report will examine trends in teaching practices several years after the training sequence ended.

| Component | Status |

|---|---|

| Baseline | Learning Infrastructure: Data collected from 2015 to 2017, in tranches as schools were rehabilitated. The baseline report was released in December 2017.

Training Educators: Data was collected in October 2017. |

| Midline | Learning Infrastructure: Data collection was completed in March 2019.

Training Educators: Data collection was completed in October 2018. The Interim Report was published in August 2019. |

| Endline | Learning Infrastructure: Data collection will be completed in 2022.

Training Educators: Data collection was completed in September 2019. The Final Evaluation Report is expected in 2023. |

- Construction timelines for the Improved Learning Environment Activity were significantly longer than originally anticipated. For future school infrastructure investments MCC should stress realistic work planning from the start of the compact.

- The success of the TEE Activity in reaching its participation targets across Georgia was due to a great deal of collaboration between the MCA, Program Management Unit (PMU) within the Teacher Professional Development Centre (TPDC), and Program Management Consultant, IREX.

- Stakeholder input is critical to survey module design and made the TEE data more useful to both MCC and the Ministry of Education and Science. Future evaluations should plan time for a survey design workshop in country.

Key Output and Outcome Indicators

| Key Performance Indicators | Baseline | End of Compact Target | Q1-Q20 Actuals (as of July 2019) | Percent Target Satisfied |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational facilities constructed or rehabilitated | 0 | 130 | 91 | 70% |

| Science labs installed and equipped | 0 | 130 | 91 | 70% |

| Students benefitting from rehabilitated school buildings | 0 | 37,450 | 39,830 | 106% |

| School-based professional development facilitators who complete Leadership Academy 3 | 0 | 1,528 | 1,409 | 92% |

| School principals who complete Leadership Academy 1 | 0 | 1,668 | 1,823 | 109% |

| Teachers who have completed Core Module 3 | 0 | 14,578 | 14,859 | 102% |

| Teachers who completed the full course and received a certificate | 0 | 13,666 | 11,829 | 87% |

| National assessments developed and implemented with MCC funding | 0 | 10 | 6 | 60% |

| International assessments developed and implemented with MCC funding | 0 | 5 | 6 | 120% |